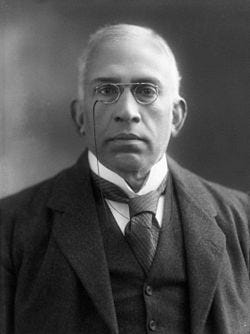

In the spring of 1919, as blood soaked the earth of Jallianwala Bagh and the colonial machinery closed ranks to defend its brutality, one man chose to dissent—not with weapons, but with conscience. Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, a distinguished jurist and member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, shocked the British establishment by resigning in protest. His bold repudiation of the massacre was not merely a political gesture; it was an act of moral resistance that cracked the imperial façade.

He served as the Advocate-General of Madras from 1906 to 1910, on the High Court of Madras as a puisne justice from 1910 to 1915, and as India-wide Education minister as a member of the Viceroy's Executive Council from 1915 until 1919. He was elected president of the 1897 Indian National Congress, and led the Egmore faction, opposing the Mylapore group.

V. C. Gopalratnam’s assessment places Sankaran Nair in the upper echelons of the Madras legal fraternity—just a step behind titans like Sir Bhashyam Aiyangar and Sir Subramania Iyer, and shoulder to shoulder with other luminaries of the Egmore faction. It’s a testament not only to Nair’s legal acumen but also to his stature as a nationalist intellectual who could challenge colonial orthodoxy from within its own institutions.

His book Gandhi and Anarchy (1922) is a fascinating counterpoint to the dominant nationalist narrative. In it, Nair critiques Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement, arguing that it risked destabilizing India’s constitutional progress and could lead to lawlessness if not tempered by pragmatic reform. He also used the book to hold Lt. Governor Michael O’Dwyer accountable for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which led to the infamous libel trial in London.

Born into the distinguished Chettur lineage in Mankara, Palakkad on 11 July 1857 to Parvathy Amma Chettur and Mammayil Ramunni Panicker, a tahsildar under the British Govt, of the Mammayil family, in Mankara, Palakkad district. He got his name as per the matrlineal traditions of the Nairs.

Educated first in the quiet rhythms of traditional Malabari learning, and later at Provincial School, Kozhikode and Presidency, Madras, Sankaran Nair's intellectual journey was as hybrid as the India he sought to reform. By 1879, armed with degrees in arts and law, he stepped into the legal arena—an arena where he would soon challenge the very empire that had shaped his early path.

He began his career as a lawyer in 1880 in Madras HC, and in 1884 the Government appointed him as a member of the committee for an enquiry into the district of Malabar. He was the Advocate-General to the Government till 1908, and later became a permanent Judge in the Madras HC where he served till 1915.

His role in the Collector Ashe murder trial (1911–12) placed him at the heart of a politically charged case. While the majority of the bench convicted the accused, he dissented, arguing that convictions based solely on uncorroborated accomplice testimony were legally unsound. His dissent became a landmark in evidentiary jurisprudence and a subtle act of resistance.

In his most cited judgment, he ruled that conversion to Hinduism did not render one an outcast, challenging entrenched caste orthodoxy and affirming religious freedom.

He founded and edited the Madras Review (1895–1905) and the Madras Law Journal, both of which became platforms for legal and social reform. While Madras Review tackled issues ranging from education policy to constitutional reform, Madras Law Journal remains a respected legal publication even today, cited in Indian courts.

Appointed as Secretary to the Raleigh University Commission in 1902 by Lord Curzon, Nair helped shape recommendations for reforming Indian higher education.

Though initially dominated by British officials, Indian members like Sankaran Nair, Syed Hussain Belgrami, and Gurudas Banerjee were later added under pressure.The Commission’s work led to the Indian Universities Act of 1904, which controversially increased government control over universities, but also standardized curricula and examinations.

In 1904, he was made a Companion of the Indian Empire (CIE)—a rare honor for an Indian at the time. In 1912, he was knighted, becoming Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, further cementing his stature within the colonial establishment.

As Education Member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council (1915–1919), Nair authored two powerful Minutes of Dissent in response to the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms.

He criticized the reforms for undermining Indian representation in legislative council, retaining excessive executive control over “Transferred Subjects.” and dismissing nationalist demands as coming from a “small and insignificant class.”

His dissent argued for greater Indian autonomy, equal representation, and constitutional accountability—a bold move for someone within the system.Remarkably, many of his recommendations were accepted, showing the persuasive force of his arguments.

April 13, 1919

The massacre at Jallianwala Bagh during Baisakhi, a harvest festival and day of spiritual renewal for Sikhs, turned a moment of celebration into one of unprecedented horror.

Thousands had gathered at the walled garden of Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar to protest the Rowlatt Act, which allowed indefinite detention without trial. Without warning, Brigadier General Reginald Edward Dyer ordered his troops to open fire on the unarmed crowd. They blocked the only narrow exit and fired for 10 minutes, expending over 1,600 rounds, killing at least 379 civilians (according to British figures)—though Indian estimates place the toll much higher.

The massacre sent shockwaves across India and the world. Gurudev Tagore renounced his Knighthood in protest. Gandhi called off his first mass non-cooperation campaign, shaken by the violence. It catalyzed radicalization among freedom fighters—Udham Singh would later assassinate Michael O’Dwyer, the Punjab Lieutenant Governor who endorsed Dyer's actions.

"If to govern the country, it is necessary that innocent persons should be slaughtered at Jallianwala Bagh and that any Civilian Officer may, at any time, call in the military and the two together may butcher the people as at Jallianwala Bagh, the country is not worth living in" - C. Sankaran Nair

As Education Member of the Viceroy’s Council, Sir Sankaran Nair immediately resigned in protest, a rare act of defiance from within the colonial administration.

That moment of resignation wasn’t just a political act—it was a rupture in imperial decorum. Sir Sankaran Nair’s decision to step down from the Viceroy’s Executive Council after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre was unprecedented. But what followed was equally daring.

He reached out to the editor of The Westminster Gazette, a liberal British newspaper known for its reformist stance.The resulting article, titled “The Amritsar Massacre,” broke through the veil of colonial censorship and brought the horrors of Punjab to British drawing rooms. The Times and other major papers soon echoed the coverage, amplifying the outrage and forcing the British public to confront the brutality of their empire.

At a time when martial law and press blackouts had sealed off Punjab, Nair’s intervention ensured that the massacre could not be buried in silence.His actions helped catalyze the formation of the Hunter Commission, and laid the groundwork for international scrutiny of British rule.

In his 1922 book 'Gandhi and Anarchy', Nair wrote about following the events in Punjab with increasing concern. He wasn’t merely reacting to the massacre—he was documenting a systematic silencing of Punjab, where martial law became a cloak for unchecked brutality.

After the Jallianwala Bagh massacre on 13 April 1919, the British imposed martial law across key districts: Amritsar, Lahore, Gujranwala, Gujarat, and Lyallpur. The region was sealed off—telegraphs censored, newspapers banned, and public gatherings outlawed. Punishments were grotesque: public floggings, crawling orders, and forced salutes to British officers.

Nair wrote with increasing alarm about the total blackout of information from Punjab. His critique wasn’t just about Dyer’s bullets—it was about the entire colonial machinery that enabled and then concealed the violence.Nair argued that the Rowlatt Act, martial law, and the suppression of press were part of a deliberate strategy to crush dissent.

He accused Sir Michael O'Dwyer, the former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, of state-sponsored terrorism, holding him accountable for the brutalities committed by the civil administration before martial law was declared. He also alleged that O’Dwyer used coercive recruitment tactics during WWI, and enabled and endorsed atrocities like public floggings, crawling orders, and indiscriminate shootings.

O'Dwyer in turn retaliated with a libel suit in London’s King’s Bench Division in 1924, claiming defamation. The case became a proxy trial for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and the wider repression in Punjab.

After a five-week trial in the Court of King's Bench in London, ruled 11:1 in favor of O'Dwyer, awarding him £500 in damages and £7,000 in costs. However Nair refused to offer an apology—choosing instead to pay the penalty and preserve his moral stance.

The Case That Shook the Empire, co-authored by Raghu Palat and Pushpa Palat, offers a deeply personal and meticulously researched account of the 1924 libel trial. Drawing from daily reports in The Times and family archives, the book reconstructs how Sir Sankaran Nair’s courtroom battle became a catalyst for nationalist awakening

After the trial, Nair served as a councillor to the Secretary of State for India in London—a role that gave him access to the heart of British policymaking. From 1925, he became a member of the Indian Council of State, the upper house of the Imperial Legislative Council, where he continued to advocate for constitutional reform and Indian autonomy.

He played an active part in the Nationalist movement which was gathering force in those days. In 1897, he resided over both the First Provincial Conference in Madras and the Indian National Congress session at Amravati, where he boldly demanded Dominion Status—a radical call for self-rule at the time.

He joined the Madras Legislative Council in 1900, contributing to debates on education, caste reform, and village governance. And in 1928, he led the Indian Central Committee to engage with the Simon Commission, preparing a detailed report advocating Dominion Status. While many boycotted the Commission, Nair believed in strategic engagement to push reform from within.

True to the matrilineal customs of the Nayar aristocracy, he was married young to Palat Kunhimalu Amma, also known as Parvati Amma. Her passing away in 1926 during a pilgrimage to Badrinath , in the twilight of his political career, likely deepened his introspective retreat from public life.

After the Viceregal announcement accepting Dominion Status as India’s ultimate goal, Nair felt his mission was fulfilled and retired from politics. He passed away in 1934, aged 77, leaving behind a legacy of legal brilliance, moral courage, and reformist nationalism.

Their eldest daughter Parvathi Amma (later Lady Madhavan Nair) married her cousin Sir C. Madhavan Nair, a legal luminary and a judge of the Privy Council. They lived on a large estate known as Lynwood, in Chennai. The estate now lives on in the names of roads like Lynwood Avenue, Palat Narayani Amma Road, Palat Sankaran Nair Road, and Palat Madhavan Nair Road.

She donated land for the Ayappan-Guruvayoorappan Temple in Mahalingapuram , a gesture that embedded her family’s values into the spiritual and urban fabric of Chennai. The temple, often called a “Little Guruvayur,” became a vital center for Kerala-style worship and Sabarimala pilgrimage preparations.

Saraswathy Amma (Anuji), their youngest daughter , married K. P. S. Menon Sr., India’s first Foreign Secretary and a towering figure in the Indian Civil Service. He was also a diarist and ambassador to China, the Soviet Union, and several other nations.

Their son, K. P. S. Menon Jr., followed in his father’s footsteps, serving as India’s Foreign Secretary in 1987, and as ambassador to countries including China, Egypt, and Japan.

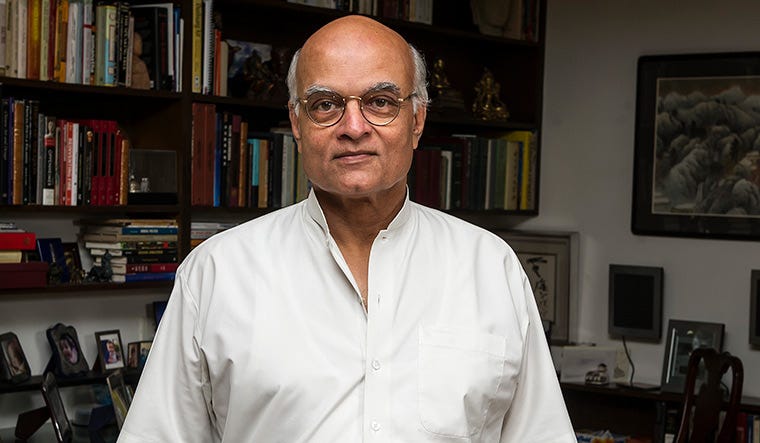

The legacy continued with Shivshankar Menon, grandson of Saraswathy Amma, who became India’s 4th National Security Advisor (2010–2014) and Foreign Secretary (2006–2009). He also served as ambassador to China, Israel, and High Commissioner to Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Their only son Ramunni Menon Palat, carved out a distinct political identity. He was a Barrister-at-Law and a prominent landholder (Jenmi) from Kerala.

He represented the Westcoast (Malabar) Landholder's Constituency in the Madras Legislature from 1930 to 1936, and served Minister for Public Health in Kurma Venkata Reddy Naidu’s interim cabinet (April–July 1937).

Initially affiliated with the Justice Party, which advocated for non-Brahmin rights and opposed Congress dominance, he later joined the Hindu Mahasabha, reflecting a complete shift in ideology.

His great granddaughter Divya Palat, was a noted actress, who appeared in the TV series Captain Vyom, and appeared in a couple of movies like Masti, Kuch Na Kaho, Krishna Cottage.

His another grandson Lt. Gen. Kunhiraman Palat Candeth, was led Operation Vijay in 1961, liberating Goa, Daman, and Diu from Portuguese rule, and served briefly as Military Governor of Goa, and also commanded the Indian Army on the Western Front in the 1971 War.

His other two daughters were married to M.Govindan Nair, an IPS officer, and T.K.Menon, a civil servant.

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair’s life did not culminate in the courtroom where empire tried to silence him—it echoed far beyond it. His resignation after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre was not just a principled departure; it was a proclamation that justice demands courage. And that courage flowed not only through his words, but through the generations that followed.

From Lady Madhavan Nair’s temple patronage to Lt. Gen. Candeth’s battlefield command; from K. P. S. Menon’s diplomatic finesse to Anil Menon’s voyage into the cosmos—his descendants forged paths of service shaped by intellect, conviction, and a refusal to bow. They became guardians of India’s identity, defenders of sovereignty, and explorers of new frontiers.