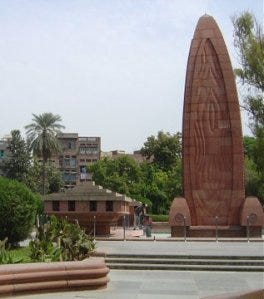

Jallianwala Bagh remains one of the most harrowing markers of colonial violence, an event that seared itself into the soul of the freedom struggle.

The Ghadr Mutiny of 1915, inspired by revolutionaries abroad, aimed to ignite a pan-Indian revolt. Though ultimately suppressed, it sent waves of unease through the Raj. In its aftermath, the Defence of India Act was passed—effectively granting sweeping powers of preventive detention and censorship. It marked the beginnings of a surveillance state.

By 1919, with nationalist unrest growing, the British doubled down with the Rowlatt Act—an extension of wartime restrictions into peacetime, which Mahatma Gandhi called a "Black Act."

Michael O' Dwyer, then Lt Governor of Punjab, was one of the strongest supporters of the Defense of India Act, with the state in the throes of a total revolt. He wasn’t just an administrator—he was an ideologue. Under his governance, Punjab resembled a powder keg, and instead of easing tensions, he tightened the screws. His unflinching endorsement of the Defence of India Act created a legal scaffold for authoritarianism, all under the pretext of wartime exigency. To him, revolutionaries weren’t political actors—they were threats to be eliminated. It's no accident that he later justified Jallianwala as necessary to "save the Raj."

While Indian soldiers fought valiantly in Europe, Mesopotamia, and East Africa, during WW1, that broke out around that time, it was badly affecting India in many ways.

On one side heavy taxation drained already scarce rural economies, disruption in trade that devastated local industries and artisans, and forcible recruitment which took a heavy emotional and social toll.

India had paid in blood and coin, and yet was met with curfews, censorship, and lathi charges when it hoped for dignity in return.

The Rowlatt Act of 1919—dubbed the “Black Act”—was the British Raj’s attempt to legitimize tyranny under the veneer of legality. Despite the end of WWI, it extended wartime powers with no jury trials, incarceration without evidence or appeal, and censorship.

It effectively criminalized dissent. Even moderates like Jinnah—once seen as a constitutionalist—found this unbearable. His resignation was not just political; it was a moral outcry.

Punjab erupted in protest, The sense of betrayal was raw and personal. People weren’t just resisting a law—they were protesting a systematic stripping of their dignity. Lahore turned into a flashpoint of marches and clashes, whilerRail lines, telegraph wires—the arteries of the Raj—were cut. And in Amritsar, over 5,000 people defied curfews to assemble peacefully at Jallianwala Bagh.

This wasn’t chaos—it was courage. The land that once gave rise to saints and soldiers now birthed resistance from every street corner and field.

Prior to Jallianwala Bagh, there was a large protest in Amritsar on April 10, 1919 at the residence of the Dy. Comissioner. The detainment of Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr. Satyapal, both deeply respected, was a deliberate provocation by a colonial regime that feared ideas more than armies. The crowd’s plea wasn’t just for their release—it was a cry for dignity, for visibility.

The crowd at the Deputy Commissioner’s residence came with grievances, not arms. But the regime met them with bullets. The violence that followed—banks aflame, British symbols attacked—wasn’t orchestrated anarchy. It was an eruption of grief and fury, spontaneous and raw.

The British narrative often reduces this to mob violence. But at its heart was a people stripped of avenues to express outrage within the system.

Banks, the Town Hall and many Govt buildings were attacked and set on fire by the protestors. 5 Europeans were killed in the ongoing clashes, while around 20 Indians were killed in the firing. While Amritsar was somewhat quite on the following days, the rest of Punjab continued to burn. Railway lines were cut, telegraph posts destroyed, Govt buildings attacked.

By April 13, Punjab wasn’t just rebellious. It was occupied. Martial law didn’t restore order—it broadcast fear.

April 12, 1919

A meeting was held in Amritsar, Hans Raj, an aide to Dr. Kitchlew, that was a collective act of defiance to announce a large scale protest meeting at Jallianwala Bagh the next day. After the trauma of April 10, and with the city humming under martial law, that gathering—called not in secrecy but in public—spoke volumes. Hans Raj’s announcement carried with it both hope and danger.

Organized by Mohd Bashir and Kanhaiya Lal, stalwarts of the Punjab Congress, the call to assemble at Jallianwala Bagh wasn't just about protesting the arrests—it was about reclaiming public space, about refusing to be cowed. That they dared to name the place, name the time, and march in defiance of the ban… it shows a society on the cusp of transformative reckoning.

And then comes the irony that still haunts the conscience of a nation—Jallianwala, a literal “garden of the Jallianwala family,” a space associated with community and calm, would become a killing ground by the next afternoon.

April 13, 1919

Baisakhi had drawn thousands to Amritsar. Pilgrims came to bathe at the Golden Temple, families thronged the streets in celebratory attire, and for many, Jallianwala Bagh was simply a place to rest, to gather, to listen. There was no inkling that joy would soon be outlawed.

Col Reginald Dyer had had already posted curfew notices and banned public meetings—but many never saw the proclamations, or didn’t believe such brutality could occur. Around 3:30 pm, he arrived with 90 soldiers, Gurkha and Baluchi rifles in hand. They entered through the only viable exit.

Jallianwala Bagh is roughly around 200 by 200 yards in size, surrounded by 10 feet walls, and houses overlooking it. There was a well, a small cremation ground, and just one narrow entrance to it. The place was a veritable death trap.

Dyer’s intention wasn’t crowd control. It was colonial theatre—a spectacle of power meant to discipline not just Amritsar, but all of India. In his own words, he saw it as a “moral lesson”. He fired not until the crowd scattered, but until his ammunition was nearly exhausted.

Around 4:30 PM, Dyer arrived at Jallianwala Bagh with a force of around 90 soldiers, mostly Sikh, Gurkha and Baluchi. Armed with .303 Lee-Enfield bolt rifles, 2 armored cars with machine guns, which however cud not enter inside.

It had around 5 entrances to it, of which only one was in use, and that too a narrow one. Surrounded by houses on all sides, nowhere to go really, a complete death trap.

Dyer’s actions were no spur-of-the-moment reaction. He blocked the exits, surveyed the crowd, and gave the fateful command. The rifle muzzles were not scattered—they were aimed, targeting the densest parts of the crowd. When questioned later, he didn’t equivocate:

“It was not my duty to disperse the crowd. I was going to punish them.”

That well—once a source of life—became a grave. It embodied the sheer desperation of those minutes, the instinct to flee even into death rather than face the guns. Later, they pulled out over 120 corpses from it. A silent cenotaph to innocence.

That well stands not just as a physical site, but as a silent scream, echoing across generations. The desperation it witnessed—the choice between certain death by bullet and the desperate plunge into darkness—defies comprehension. It's one thing to read numbers in textbooks; it’s another to imagine a mother clutching her child, leaping into that abyss in terror.

While numbers were not known, it is estimated around 1500 people died in the horror at Jallianwala Bagh. More than the numbers it shattered the myth of the “civilized British”. Gen Dyer was a monster, who had no guilt about his actions.

Following the massacre, Punjab didn’t receive relief—it was buried under martial law. And under that cloak, the British unleashed a reign of degradation.

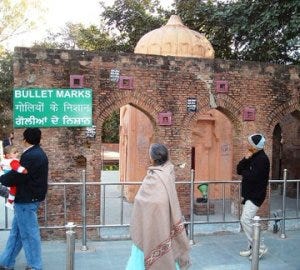

Public floggings became spectacles of power. Crawling orders were issued—most infamously on Kucha Kurrichhan Wali Gali in Amritsar, where Indians were forced to crawl on their bellies for daring to walk a street where a British woman had been attacked. Indiscriminate arrests, mass detentions without trial, and whipping stations were installed.Even press reporting was censored—truth itself was shackled.

“Some Indians crawl face downwards in front of their gods. I wanted them to know that a British woman is as sacred as a Hindu god and therefore they have to crawl in front of her, too.”

In the House of Commons, Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for War, delivered one of the most scathing rebukes:

“The incident in Jallianwala Bagh was an extraordinary event, a monstrous event, an event which stands in singular and sinister isolation…”

Around 247 MPs voted to censure Dyer’s actions, forcing him to resign. This was rare—it wasn’t often the British Parliament turned against its colonial enforcers.

Gurudev Tagore renounced his knighthood in protest against the massacre.

I … wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings. -Rabindranath Tagore.

Despite this, a fund of over £26,000 (equivalent to millions today) was raised by public subscription in Britain, spearheaded by right-wing outlets like The Morning Post, praising Dyer for "saving the empire." Dyer was portrayed not as a butcher, but as a bulwark against disorder. It revealed how the British public, largely insulated from the realities of empire, clung to myths of righteous dominion.

That some Sikh priests granted Dyer a saropa—a ceremonial robe of honor usually reserved for spiritual merit—deepens the tragedy. It wasn’t a blanket endorsement, and many Sikhs fiercely opposed the gesture. But it underscores how fractured the response to colonial violence could be, especially under intense imperial pressure and fear.

Called for enquiry before the Hunter Comisssion, Gen Dyer, had the least remorse on his act. He clearly stated that his intention was to unleash a reign of terror in Punjab. And he stated he did not stop shooting, till ammunition was exhausted.

” Supposing the passage was sufficient to allow the armoured cars to go in, would you have opened fire with the machine guns?”

Gen Dyer- Yes

In that case much higher casualties”.

Gen Dyer- Yes

Colonel Reginald Dyer, the Butcher of Amritsar, the face of pure evil, and this is what he had to say

“Its only enlightened people who deserve freedom, Indians want no such enlightenement”

And never ever forget all those who died at Jallianwala Bagh, it was darkness on Baisakhi. Every Indian should ensure that at least once in their lifetime, they make a visit to Jallianwala Bagh, stand there, feel the horror of that fateful day, look at the bullet marks in the walls. You will come out of it totally overwhelmed.