Komagata Maru, a name that resonates in the history of India’s freedom struggle. The Japanese steamship carrying Indians trying to migrate to Canada in 1914, majority of whom were Sikhs, along with a fairly good number of Hindus and Muslims, all from Punjab. Only 24 of the 376 passengers were admitted, while the rest were turned back and the ship had to return to Kolkata.

The British police tried to arrest the group leaders, leading to clashes and firing which left around 20 dead. The incident bought into focus the discriminatory laws of US and Canada, that excluded immigrants of Asian origin during that time. But more than anything else, this event led to the rise of the Ghadar party, as it’s leaders Tarak Nath Das, Sohan Singh and Barkatullah, used it to recruit more members for their cause.

The visions of men are widened by travel and contacts with citizens of a free country will infuse a spirit of independence and foster yearnings for freedom in the minds of the emasculated subjects of alien rule.

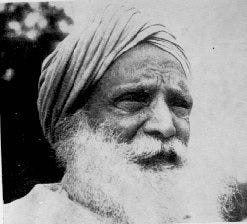

Baba Gurdit Singh was the beating heart of the Komagata Maru saga, a man whose defiance turned a voyage into a political statement.

Born in 1860 in Sarhali, Punjab, into a family with a legacy of resistance (his grandfather fought the British in the Anglo-Sikh Wars), Gurdit Singh carved his own path as a contractor and businessman in British Malaya and Singapore. But it was in 1914 that he stepped into history.

In 1885, he came to Malaya, where his father was working as a contractor. He soon began to be involved in many businesses, importing cattle from India, operating a dairy, supplying milk to a Sikh regiment stationed there. As well as contracting labor for railway work, the rubber plantations, and dealing with real estate too.

He soon became one of the well known Indian businessmen in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, and an influential member of the Sikh community there. Apart from Punjabi, he was fluent in Chinese, Malay and English which he learnt while working there.

His reverence for Baba Ram Singh, the founder of the Namdhari (Kuka) movement, reveals a profound alignment with reformist Sikh ideals. The Kukas emphasized non-cooperation with British rule, Swadeshi, and moral discipline—values that clearly shaped Gurdit Singh’s worldview.

By inviting Ram Singh to Malaya, Gurdit wasn’t just seeking spiritual solace—he was planting seeds of resistance among the diaspora, blending faith with political awakening.

In 1911, he formally complained to British authorities about the practice of begar—forced, unpaid labor imposed on villagers by colonial officials. When his pleas were ignored, he urged villagers to resist, marking one of the earliest instances of grassroots civil disobedience in British Malaya—years before Gandhi’s satyagraha gained momentum.

Gurdit Singh, already a respected figure among the Sikh diaspora, was approached by Indian emigrants stranded in Hong Kong, desperate to reach Canada before new restrictions tightened further. The Panama Maru case—where 39 Indians had briefly succeeded in entering Canada—had given many false hope.

But the Continuous Journey Regulation still loomed large, effectively barring Indian immigrants by requiring uninterrupted travel from their country of origin, which was logistically impossible.

That December 1913 meeting at the Hong Kong Gurudwara was more than a gathering—it was a crucible of shared frustration, hope, and resolve, where Gurdit Singh patiently listened to their stories—of savings lost, families separated, and dreams deferred. That night, something shifted. He decided to act.

To circumvent the exclusion laws, he presented himself as a businessman launching a passenger service between Asia and North America.He chartered the Komagata Maru under the Guru Nanak Steamship Company, cloaking his mission in the language of trade while quietly rallying a movement.

By early 1914, he was openly espousing the Ghadar cause in Hong Kong, distributing revolutionary literature and aligning with figures like Maulvi Barkatullah and Gyani Bhagwan Singh. The ship became more than transport—it was a symbol of defiance, a vessel of dignity sailing into the heart of imperial hypocrisy.

Canada had passed the Continuous journey regulation order on January 8, 1908, as per which any immigrants who did not make a continous journey from their country of birth or citizenship, were prohibited from entering the country.

The order was clearly aimed at India, as ships travelling to North America usually made a stop over in Japan or China due to the large distance covered.The law was a legal sleight of hand—a way to uphold white supremacist immigration policies without violating the British Empire’s principle of equality among its subjects.

In September 1907, Vancouver witnessed violent riots led by the Asiatic Exclusion League, targeting Chinese, Japanese, and South Asian communities. Thousands marched under banners like “Keep Canada White,” smashing windows in Chinatown and Japantown, and clashing with Japanese residents who defended their homes.

Though few were prosecuted, the riots galvanized public support for stricter immigration controls, directly influencing the passage of the Continuous Journey Regulation. It was part of a broader imperial anxiety—Canada wanted to remain a “white man’s country,” but couldn’t openly discriminate against fellow British subjects from India.

By early 1914, Baba Gurdit Singh had moved beyond being a concerned community leader—he had become a conduit for revolution. In Hong Kong, he began openly endorsing the Ghadar Party, whose ideology was rooted in armed rebellion against British rule and the creation of a secular, egalitarian India.

He distributed Ghadar literature aboard the Komagata Maru, transforming the ship into a floating manifesto of resistance. Passengers were not just hopeful migrants—they were politically awakened British subjects, many of them ex-soldiers, farmers, and students, now galvanized by the Ghadar call.

The ship was renamed Guru Nanak Jahaj, a deliberate invocation of spiritual authority and moral legitimacy. It wasn’t just a name—it was a statement: that this journey was not merely about immigration, but about dharma, dignity, and defiance.

The Canadian government, already rattled by the Panama Maru case and the 1907 anti-Asian riots, viewed the Komagata Maru with deep suspicion. Intelligence reports suggested that Ghadarites were aboard, and that the ship’s arrival could spark unrest among Indian troops stationed in British Columbia.

The original March 1914 departure was stalled due to legal entanglements—notably, Gurdit Singh’s arrest in Hong Kong for allegedly selling tickets for an “illegal voyage.”

British intelligence had already marked him as a subversive figure, and his every move was under scrutiny. Yet, with quiet resolve and official permission from the Governor of Hong Kong, the Komagata Maru finally set sail on April 4 with 165 passengers.

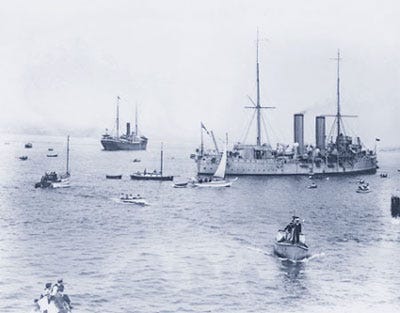

At Shanghai (April 8) and Yokohama (April 14), more passengers boarded—many of them Ghadar sympathizers or political exiles. By the time the ship left Yokohama on May 3, it carried 376 passengers: 340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims, and 12 Hindus, all Punjabis and British subjects.

The ship was now more than a vessel—it was a symbol of collective defiance, sailing into the heart of imperial exclusion.

Upon arrival at Burrard Inlet on May 23, the passengers were met not with welcome, but with hostility and suspicion.Yet, Bhagwan Singh Gyanee, the head priest of the Vancouver Gurudwara and a former deportee himself, came aboard.

He distributed Ghadar literature, pamphlets, and books, transforming the ship into a floating university of revolution.Political meetings were held on deck. The passengers, many of them ex-soldiers, were told: “This ship belongs to the whole of India… if it is detained, there will be mutiny in the armies.”

Fred “Cyclone” Taylor, a hockey legend turned immigration officer, was the first to board the ship. He informed Gurdit Singh and the captain that no passengers would be allowed ashore—a message delivered with bureaucratic calm but imperial finality.

Prime Minister Robert Borden hesitated, aware of the diplomatic implications. But British Columbia’s Premier Richard McBride was unequivocal: “No passenger will be allowed to disembark.” His stance reflected the province’s deep-rooted commitment to a “White Canada” policy.

Conservative MP H.H. Stevens, representing Vancouver, became the most vocal opponent of the passengers. He organized public meetings, stoked fears of an “Oriental invasion,” and worked closely with immigration officer Malcolm R.J. Reid to block supplies and legal access to the ship.

Stevens even prevented lawyer Edward Bird from boarding the ship to meet his client, Gurdit Singh—a move that denied the passengers their basic legal rights.

His rhetoric wasn’t subtle. He declared: “The national life of Canada will not permit any large degree of immigrants from Asia… I stand for a white British Columbia.”

Under Stevens and Reid’s direction, the passengers were denied food, water, and medical aid for days at a time. Supplies sent by the Shore Committee were often delayed or blocked entirely. The goal was clear: break their spirit, force them to surrender, and make an example of them.

Meanwhile a Shore Comittee was raised by Rahim Hussain, Balwant Singh and Sohan Lal Pathak in Vancouver, to help the passengers. It wasn’t just a support group—it was a political front, declaring that if the passengers were denied entry, there would be open revolt or Ghadr on Canadian soil. Their rhetoric wasn’t empty. The committee’s meetings echoed with revolutionary fervor, and British intelligence began to fear a diasporic uprising.

The committee raised $22,000—a staggering sum at the time—to charter the ship and mount a legal challenge. They filed a test case in the name of Munshi Singh, one of the passengers, arguing that the exclusion violated imperial rights.

However the British Columbia Court of Appeal delivered a unanimous judgmen on July 6, 1914, it had no jurisdiction to override the decisions of the Department of Immigration and Colonization. The ruling effectively sealed the fate of the passengers. Law had spoken—but it spoke in the language of exclusion.

The furious passengers relieved the Japanese captain of comand, but the Canadian Govt,ordered the tug boat Sea Lion to tow it out, amidst angry protests.

William C. Hopkinson, a former Calcutta police officer turned Canadian immigration inspector, had become the Empire’s eyes and ears in Vancouver. Fluent in Hindi but not Punjabi, he relied on a network of informants to infiltrate the Ghadar Party and monitor anti-colonial activities.

He played a central role in the Komagata Maru standoff, feeding intelligence to both Canadian and British authorities. His actions led to the harassment, arrest, and even deaths of several Ghadar sympathizers.

On October 21, 1914, while waiting to testify in court during the trial of Bela Singh (an informant who had shot two Sikhs inside the Vancouver Gurudwara), Hopkinson was shot dead in the courthouse corridor by Bhai Mewa Singh, a devout Sikh and Ghadar sympathizer.

Mewa Singh surrendered immediately, saying, “I shoot. I go to station.” At his trial, he declared he acted not out of personal hatred, but to defend the honor of his faith and community, desecrated by violence inside the Gurudwara and manipulated by Hopkinson’s espionage.

He was executed on January 11, 1915, at New Westminster Jail. To this day, many in the Sikh community regard him as a shaheed (martyr)—a man who chose death over dishonor.

Hopkinson’s assassination sent shockwaves through colonial intelligence networks. It exposed the fragility of imperial control, especially when confronted by diasporic resistance. The Ghadar Party, though ultimately suppressed, had succeeded in igniting a global consciousness—from Vancouver to Punjab, from courtroom corridors to battlefields of ideology.

On September 27, 1914, the Komagata Maru reached Kolkata (then Calcutta) after a harrowing two-month standoff in Vancouver and a long voyage back.

As it entered Indian waters, it was intercepted by a British gunboat and placed under armed guard. The colonial authorities viewed the passengers not as returning citizens, but as potential revolutionaries—a threat to imperial stability, especially with World War I underway.

The ship was diverted to Budge Budge, a small port town south of Kolkata. There, the British planned to forcibly deport the passengers to Punjab by train. But the passengers, led by Baba Gurdit Singh, refused. They demanded to first return the Guru Granth Sahib to a Gurdwara in Calcutta—a spiritual act of closure.

When police attempted to arrest Gurdit Singh and about 20 others, a violent confrontation erupted. Accounts describe a baton charge, followed by gunfire. At least 20 passengers were killed, some say more. Others were wounded, arrested, or vanished into the countryside.

After years underground, Baba Gurdit Singh surrendered at Nankana Sahib in 1920 on Mahatma Gandhi’s advice, embracing the path of non-violence and civil disobedience.

He was imprisoned for five years, released in 1925, and lived quietly in Calcutta until his death in 1954. Though he adopted Gandhian ideals, his revolutionary past remained a quiet ember, never fully extinguished.

The Indian National Congress, focused on constitutional reform and mass movements, distanced itself from the Komagata Maru episode—perhaps because of its association with armed rebellion and the Ghadar Party’s radicalism.

The Komagata Maru incident became a rallying cry for the Ghadar Party, especially among expatriate Indians in the U.S. and Canada. They used it to recruit revolutionaries, raise funds, and plan a coordinated uprising in India during World War I.

The plan, known as the Ghadar Conspiracy, aimed to incite mutiny within the British Indian Army and was supported by Germany and Indian revolutionaries like Rash Behari Bose.

The uprising was scheduled for February 21, 1915, with Rash Behari Bose and Kartar Singh Sarabha at the helm. But British intelligence, aided by informants, infiltrated the movement. The plan was foiled before it began.

Hundreds were arrested. Many, including Sarabha, were executed. Bose escaped to Japan, where he continued the struggle and later helped form the Indian National Army.

Though the uprising failed, it shook the Empire. It revealed the global reach of Indian nationalism, and the depth of diasporic solidarity.

The Komagata Maru incident, once disowned, became a symbol of resistance—a ship that never docked, but anchored itself in the soul of a nation.

In 1952, the Indian government erected a memorial at Budge Budge, inaugurated by Jawaharlal Nehru. Designed in the shape of a kirpan, it honors the passengers killed in the police firing on September 29, 1914. The base of the monument features murals depicting key moments: Baba Gurdit Singh confronting British police, Sikh men rowing ashore, and the tragic firing itself.

A stone tablet lists the names of those martyred, while another commemorates Nehru’s dedication. A tree planted by Gurdit Singh still stands nearby—a living witness to sacrifice. Adjacent to the memorial, a two-storey museum has been constructed to house photographs, documents, and artifacts from the Komagata Maru episode.

On July 23, 1989, a plaque was installed in the Sikh Gurudwara in Vancouver to mark the 75th anniversary of the Komagata Maru’s forced departure.It honors the 376 passengers—340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims, and 12 Hindus—who were denied entry despite being British subjects.

Additional plaques and monuments have since been placed in Portal Park and along the Vancouver seawall, culminating in a formal apology by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2016.