Operation Gibraltar, Pakistan’s covert attempt in August 1965 to infiltrate Jammu and Kashmir with thousands of disguised soldiers and incite rebellion against the Indian Government.

It began on August 5, 1965 at Darra Kassi, near Gulmarh where a young Gujjar, shepherd Mohammad Deen Jagir, played a heroic role in foiling this plan. While tending his cattle in the Tosa Maidan meadow near Tangmarg, he was approached by infiltrators posing as locals.

Instead of cooperating, he alerted the police, triggering a swift response from the Indian Army that led to the elimination of seven infiltrators. His actions were so impactful that he was later awarded the Padma Shri for his bravery and service to the nation.

The subsequent encounters at Galuthi in Mendhar and the capture of two Pakistani officers at Narian on August 8 revealed the scale of the infiltration. These revelations helped the Indian Army uncover the full extent of Operation Gibraltar, which ultimately backfired on Pakistan and escalated into the Indo-Pak War of 1965.

The operation was codenamed Gibraltar, and the name was chosen with deliberate historical symbolism. Pakistan’s military leadership drew a parallel to the 8th-century Umayyad conquest of Hispania, which was launched from the Rock of Gibraltar — a strategic gateway into Europe. By invoking this imagery, they hoped to frame their infiltration into Kashmir as a similarly bold and transformative campaign.

The plan involved sending thousands of armed infiltrators — many disguised as locals — into the Kashmir Valley to incite rebellion and destabilize Indian control. But unlike the historical conquest it referenced, Operation Gibraltar faltered almost immediately.

The local population, instead of rising up, largely rejected the infiltrators. Brave individuals like Mohammad Deen Jagir exposed the operation, leading to swift Indian military retaliation and eventually triggering the Indo-Pak War of 1965.

The Sino-Indian War of 1962 had left India militarily bruised and psychologically shaken. With over 1,300 soldiers killed, thousands captured, and 38,000 sq km of territory lost in Aksai Chin, the defeat was a national trauma. Nehru’s passing away in 1964 added to the uncertainty, and Lal Bahadur Shastri, though principled and resolute, was still untested in matters of war.

Sensing India’s vulnerability, Pakistan sought to capitalize. In March 1963, it signed the Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement, ceding the Shaksgam Valley — a part of Jammu & Kashmir under Pakistan’s illegal occupation — to China. This move was strategic, it cemented a military alliance with Beijing and signaled a united front against India.

In April 1965, Pakistan launched Operation Desert Hawk in the Rann of Kutch, a disputed salt marsh region. Armed with US-supplied Patton tanks, Pakistan tested India’s resolve by capturing several posts including Sardar Post, Vigokot, and Biar Bet. Though India eventually pushed back, the skirmish emboldened Pakistan’s belief that India could be overwhelmed.

In response to Pakistani aggression in Kutch, the Indian Army launched a swift counteroffensive in May 1965, capturing three strategic posts in the Kargil sector. This show of strength forced Pakistan to agree to a ceasefire on July 1, 1965, restoring the status quo as of January 1, 1965. It was a clear signal that India was not as militarily fragile as Pakistan had assumed.

Despite the setback, Pakistan doubled down. Believing that Kashmiris would rise in revolt, it launched Operation Gibraltar in August 1965, sending thousands of armed infiltrators into the Valley disguised as locals. The goal was to foment a large-scale insurgency and destabilize Indian control.

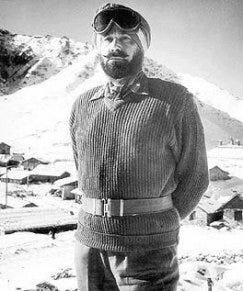

Ayub Khan, Pakistan’s self-appointed Field Marshal after his 1958 coup, believed that India’s post-1962 vulnerability and leadership transition made it ripe for a decisive strike. He entrusted Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik, a seasoned and aggressive commander, with planning and executing the operation.

Despite opposition from General Musa, the Chief of Army Staff, and other senior officers who feared escalation into full-scale war, Ayub Khan pushed forward. The plan had strong backing from Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, then Foreign Minister, who saw it as a historic opportunity to “liberate” Kashmir. Bhutto and others believed India wouldn’t risk a prolonged conflict, especially given its recent military setbacks and ongoing reorganization.

Pakistan planned to infiltrate up to 80,000 personnel, including regular soldiers and irregulars dubbed “mujahideen”, into Jammu and Kashmir. These forces were trained to blend in as locals and incite rebellion. While exact numbers vary across sources, estimates range from 30,000 to 40,000 for the actual infiltration force.

Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik, the architect of the plan, famously described its goals as:

“To defreeze the Kashmir problem, weaken Indian resolve, and bring India to the conference table without provoking general war.”

The first phase was all about creating panic and destabilization. Pakistani infiltrators — disguised as locals and dubbed “mujahideen” — were tasked with raiding key infrastructure like bridges, communication lines, and supply routes,spreading propaganda to incite rebellion, assassinating local leaders and disrupting governance and triggering mass unrest to make the Valley ungovernable.

Once the uprising was underway, Pakistan planned to merge it with direct military intervention. Regular Pakistani troops would cross the Cease Fire Line (CFL) under the guise of supporting the “freedom fighters”.

India would be forced to fight on two fronts — against infiltrators and a supposed civilian revolt.The chaos would tie down Indian forces, making a swift response nearly impossible.

Pakistan envisioned a scenario where India would be trapped in a prolonged insurgency in Kashmir — much like the U.S. in Vietnam. The hope was that adrawn-out conflict would attract global attention.

The United Nations would intervene diplomatically.India would be forced to negotiate, ideally under pressure and unfavorable optics.This was not just military strategy — it was psychological warfare aimed at shaping international perception.

According to military accounts, General Akhtar Hussain Malik began laying the groundwork for Operation Gibraltar around mid-May 1965. His approach was aggressive and ambitious. Mobilizing thousands of infiltrators and irregulars, planning multi-phased sabotage and insurgency operations and coordinating with political leadership, especially Z.A. Bhutto, who strongly backed the plan.

Pakistan’s leadership however overestimated its own military strength, especially in terms of logistics and sustainability and underestimated India’s resolve and capability, particularly the Indian Army’s ability to regroup post-1962.

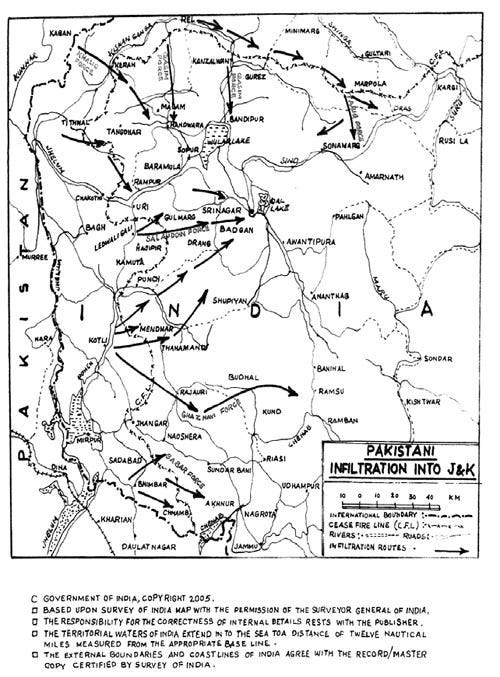

The infiltration was to be done through 10 task forces, each assigned for a particular sector in the Valley. These units were named after well known Muslim rulers, Salahaddin, Babur, Ghazni, Khilji, and they were as follows.

Salahaddin-Sringar Valley, after the Ottoman Sultan

Ghaznavi-Mendhar-Rajauri, after Mohd Ghazni

Tariq- Kargil-Drass, after Tariq Ibn Ziyad, who commanded Ummayad invasion of the Iberian Peninsula.

Babur- Nowshehra, after the first Mughal emperor.

Qasim- Bandipura, after Mohd Bin Qasim.

Khalid- Naugam, after Khalid Ibn al-Walid, who served as commander under Prophet Mohammed.

Nusrat- Tangdhar, after Nusrat Al-Din

Sikandar- Gurais, after Sikandar Lodi

Khilji- Minimarg, after Allauddin Khilji

These units were primarily made up of officers and men from POK, for better command and control. Almost 70% of the force was made up of Razakars living in POK,mostly civilians living close to the border. Each task force had 5–6 units under it, and commanded by a Pakistani Army major. Each company was commanded by a Pakistani Army Captain and comprised of JCOs, Razakars, personell from POK battalions, and it’s strength was around 120.

The units were armed on a large scale, with a huge amount of rifles, Sten carbines, LMGs, while some of the companies had 2–3″ mortars too. The personell were all asked to dress in the traditional green mazari shirt, salwar along with jungle boots to avoid suspicion. They were also given fake ID cards, Indian currency to make purchases, rations to last enough for the operation.

The Murree assembly in July 1965 was a defining moment — where Field Marshal Ayub Khan personally addressed the Gibraltar Force commanders, instilling in them a sense of historic purpose. Just days later, on August 1, Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik rallied the troops with a fiery speech, declaring this the best opportunity to “liberate” Kashmir.

The plan was two-pronged,one where disguised as locals, the infiltrators were to blend into the population, spread propaganda, and spark a civilian uprising. Their presence was meant to simulate a grassroots rebellion, making it appear as though Kashmiris themselves were revolting

Simultaneously, Pakistani forces would launch covert attacks targeting, bridges and tunnels to sever supply lines, airfields to cripple aerial response, logistics hubs and communication centers to paralyze coordination. And all targets were concentrated along the Line of Control (LOC) within the Kashmir Valley.

Thanks to early intelligence reports, the Indian Army was able to,pre-position patrols and surveillance units,intercept infiltrators before they could organize and launch rapid counter-infiltration operations, neutralizing many task forces within days.

The operation hinged on the assumption that Kashmiris would rise in revolt. But in reality, most locals refused to cooperate, and many actively reported infiltrators. Only in Mandi, Narian, and Budhil did the infiltrators receive limited support, which was far too scattered to sustain momentum.

The infiltrators were spread too thinly across vast and rugged terrain, each task force operated in isolation, with limited communication.Many units lacked logistical depth, and their movements were easily tracked.The plan failed to account for India’s terrain familiarity and rapid mobilization

On August 13, Pakistani infiltrators struck a Kumaon Regiment base, tragically killing the Commanding Officer. Though brief, the attack was,a psychological blow meant to disrupt morale and a tactical attempt to divert Indian attention from broader infiltration routes.

But the Indian Army’s response was swift and strategic. Recognizing the scale of the threat, the Army, established a dedicated HQ to manage counter-infiltration and appointed Maj Gen Umrao Singh to lead operations, known for his calm decisiveness and operational clarity.

The 19 Infantry Division, under Maj Gen Swarup Singh Kalaan, repositioned to Baramulla, from where they planned offensive strikes into infiltration zones. The division later played a key role in capturing Haji Pir Pass, a strategic victory that turned the tide of the conflict.

Under the cover of night, on August 14, Maj Balwant Singh led 17 Punjab in a daring assault to recapture Point 13620, a strategic height overlooking the Srinagar–Leh highway. The attack was executed with stealth and precision and by 0530 hrs on August 15, the post was back under Indian control.This victory was crucial in sealing infiltration routes and asserting dominance in the Kargil sector.

While Kargil celebrated, tragedy struck at Dewa, near the Chhamb sector, Brigadier Behram Master, Commander of 191 Infantry Brigade, was giving orders when a Pakistani artillery shell hit an ammunition dump. The explosion was catastrophic, killing the Brigade Commander and several officers, and it occurred at 10:00 AM on August 15, just hours after the Kargil success.

In response to escalating infiltration, Gen J.N. Chaudhuri (Chief of Army Staff) and Lt. Gen Harbaksh Singh (Western Command) met on August 17 in Jammu to, assess the operational landscape across J&K, coordinate inter-divisional strategy, especially between 15 Corps and 19 Infantry Division and lay the groundwork for a decisive counter-offensive

Lt. Gen Kashmir Singh Katoch, GOC of 15 Corps, reported that, six distinct infiltration columns were active across the Valley, operating under codenames like Salahuddin, Babur, Ghaznavi, and others, spreading across Tangdhar, Naugam, Rajauri, Kargil, and more. This intelligence was the final trigger.

Lt. Gen Harbaksh Singh, commanding Western Command, recognized that merely repelling infiltrators wasn’t enough. He ordered 15 Corps, under Lt. Gen K.S. Katoch, to capture Haji Pir Pass, which was the logistical lifeline for infiltrators entering via the Pir Panjal range, intending to cut off supply routes and seal the infiltration corridor.

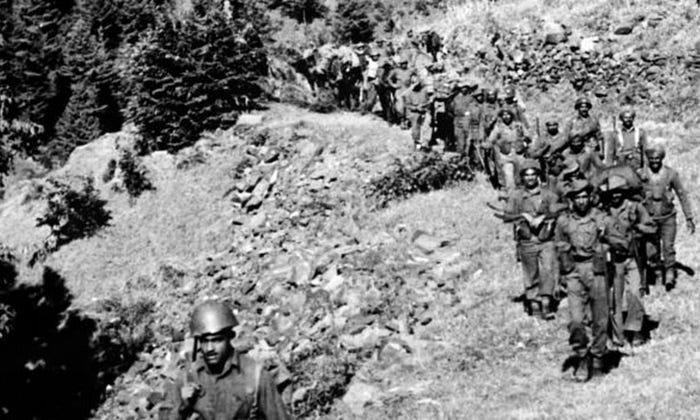

From August 26–28, Indian forces launched a daring assault, with 1 Para, led by Maj Ranjit Singh Dyal, scaling steep terrain in darkness and rain and capturing Sank, Sar, and Ledwali Gali, then pressed on to seize Haji Pir Pass itself. Pakistani forces were outflanked and fled, leaving behind weapons and supplies

Simultaneously, Indian troops advanced into the Kishanganga Bulge, dominating infiltration routes near Tithwal.17 Punjab recaptured Point 13620 in Kargil, securing the Srinagar–Leh highway.

With these victories, India sealed off key ingress routes used by Operation Gibraltar. The infiltrators were isolated, demoralized, and neutralized and the Army now held terrain advantage, enabling deeper counter-offensives.

Coming just three years after the 1962 debacle, Gibraltar was, India’s first major test of military resilience post-rebuilding.A challenge that required rapid mobilization, terrain mastery, and civil-military coordination saw the leadership turning the tide with clarity of purpose.

The credit here goes to Lt.Gen Harbaksh Singh, whose decision to capture Haji Pir Pass was not just tactical — it was visionary. He understood that cutting off the logistical artery would collapse the infiltration network.

His leadership ensured that India dictated the tempo of the conflict, as the capture of Haji Pir became the symbol of India’s resurgence, a surgical strike before the term was coined.

This wasn’t just a military win — it was a restoration of national confidence. The Indian Army, proved its adaptability and grit, showed that strategic clarity could overcome surprise and delivered a message that India would not be coerced or cornered.

Sources

Operation Gibraltar — An Unmitigated Disaster? — Criterion Quarterly

How a Kashmiri tribesman foiled Pak’s Operation Gibraltar and won over his lady love

indianarmy.nic.in/writereaddata/documents/Articles1965/PkchakGurmeet Kanwal230915.pdf

INDO PAK WAR 1965 — The Official Home Page of the Indian Army

Operation Gibraltar: How Pakistan Army’s Covert Infiltration Plan To Seize Kashmir Ended In Failure