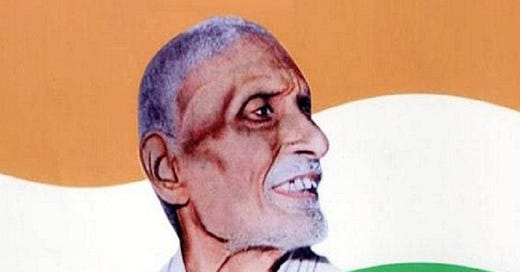

The Tiranga is more than just fabric fluttering in the wind; it's a living emblem of India's soul. And the man behind this powerful symbol is Pingali Venkayya, a name that deserves far more recognition than it often receives.

A freedom fighter, linguist, and polymath from Andhra Pradesh, Venkayya first proposed a national flag in 1921. His original design featured saffron denoting renunciation, while green depicted relation to soil, along with a spinning wheel (charkha) at the center symbolizing self-reliance and the Swadeshi movement. At Mahatma Gandhi’s suggestion, he added a white band for peace and representing the path of truth for conduct.

Over time, the flag evolved and the Ashoka Chakra, symbolizing eternal progress and righteousness, replaced the charkha in 1947 when the flag was officially adopted.

Venkayya’s legacy is stitched into every fold of the Tiranga. And yet, his story often remains in the shadows.

Pingali Venkayya was born on August 2, 1876 in small village near Machilipatnam. His father Hanumantha Rayudu was the village Karanam of Yarlaggada , while his grandfather Adivi Venkatachalam was the Tahsildar of Challapalli Samsthanam.

He studied in Hindu High school, of Machilipatnam, and later in Colombo. At the age of just 19 he joined the Army and took part in the Boer War. On his return he worked as plague inspector for some time in Madras and later Bellary.

He did his degree in Political Economics from Colombo, and later joined DAV Lahore, where he learnt Sanskrit, Urdu, Japanese. In fact so fluent was he in Japanese, that people called him “Japan Venkayya”.

He had a long association with Gandhi, having met him in South Africa earlier. He used to regularly attend all Congress session from 1913, and discuss with the leaders about the possible design of the National flag.

He also wrote a book “National flag for India”. And in 1916, the flag he designed was flown at the Lucknow session of Congress. The original flag had only 2 colors,Saffron and Green, it was Lala Hansraj who suggested a wheel in the center.

During the 1921 Vijayawada session, Gandhiji suggested adding white in between Saffron and Green, along with the wheel. And the tricolor as we know today was flown for the first time there, designed by Pingali Venkayya.

During the Constituent Assembly held on July 22, 1947, the suggestion was made to replace the wheel with the Ashoka Chakra, to represent our ancient culture.

Apart from the National flag, Pingali Venkayya, also played a role in many of the movements during freedom struggle, the Vandemataram movement. Home Rule. He had an undying passion for knowledge, and was always restless in his quest for learning.

A polyglot who was fluent in Telugu, English, Hindi, Sanskrit, Urdu and Japanese, Pingali Venkayya, also did a lot of extensive research on Japanese history, culture and language. He was an authority in that subject during his tenure at DAV.

He was equally passionate about Science, he did a lot of research on different varieties of cotton at Nadiguda( near Suryapet), on the request of the local Zamindar there. He came up with a special kind of cotton called Cambodia cotton.

He got the nickname of “Patti Venkayya”( Patti is Telugu for cotton). Matter of fact it was at Nadigudi that he designed the National flag, did prayers at the Ramayalam there, before introducing at the 1921 Congress session in Bezawada.

His biography of Sun Yat Sen, the father of modern China, shows a mind deeply attuned to revolutionary thought beyond India. It’s rare to see an Indian nationalist from that era engaging with pan-Asian modernism, much less documenting it. That connection between India and China—two ancient civilizations at turning points—must’ve resonated deeply with him.

His geological research in Mica-rich Nellore and the gemstone-laden ridges of Hampi reveals a love not just for the skies of freedom but the soil of heritage and abundance.

The fact that he authored Vajrapu Tallirayi (“Motherlode”)—what an evocative title—is poetic in itself. It roots him as someone who didn’t just honor India symbolically through the flag, but materially through its minerals, its memory, its prosperity.

After independence, Pingali Venkayya, was appointed as consultant to the Minerals Research Department, a post in which he worked till 1960, before retiring. Sadly such a brilliant scholar and genius, had a rather sad ending to his life.

A man who mapped the soul of the nation in saffron, white, and green; who spanned cotton fields and revolutions, Sanskrit hymns and Japanese texts, minerals and manuscripts—reduced in his last years to loneliness and obscurity. It’s the cruel irony that history often tucks its most luminous minds into the footnotes.

Forget about financial support, Pingali Venkayya was not even given due credit, for designing the national flag. The man who dedicated his life to the nation, had to live like a destitute in his last years, not even having proper food to eat.

What stings most isn’t just the poverty he endured, but the indifference—that a man who embodied the very ideals the flag stands for was allowed to fade into silence while the flag soared.

It’s almost as if his body was left behind while his soul continued to ripple across the skies. No martyr's salute. No footnote in textbooks. Just a hut, a whisper, and the kindness of a few—Dr. K.L. Rao, Katraggada Srinivasa Rao—who refused to let him vanish completely into the dust of history.

That final request of Pingali Venkayya, to have the flag tied to a Raavi tree after his cremation, is profoundly symbolic. The Raavi—sacred, enduring—becomes in this context not just a tree, but a silent witness. A guardian of memory. A stand-in for a nation that forgot too long, too deeply.

“Cover me in the flag. Let the tree hold it when I can no longer do so.”

That wasn’t just a final wish. It was a benediction. A quiet indictment. And a plea to be remembered.

Pingali Venkayya Gaaru, was a true son of Bharat, of whom we should all be proud. Not just as designer of national flag, but also his research on cotton, minerals.

A polyglot and a scholar, who selflessly served the country without expecting anything. A truly great soul. It is sad, that a true patriot, scholar like him , who selflessy served the nation, had to live the last days of his life in such a miserable state.