Jharkhand whose name literally means “Bush land” or “Forest land” had a long history of resistance to the British colonial rule. Among the numerous tribes that make up the state, the Santhals are one of the dominant ones, primarily in the south eastern part of the Chotanagpur plateau and Midnapore in West Bengal.

Who were the Santhals?

The Santhals are so called, as they were believed to be inhabitants of Saont , meaning plain land in Bengal’s Midnapore region. There are various theories about their origin, as per folklore they came from Hihri, which is current day Ahuri in Hazaribagh district. From there they were moved out to the Chota Nagpur plateau, and later Jhalda, Paktum.

During the Great Bengal famine of 1770, the Junglemahal region located in the South West was one of the worst hit, and many perished. The massive loss of life resulted in a significant loss of revenue for the East India Company.

So when the Permanent Settlement Act was enacted by Lord Cornwallis in 1790, the British looked for pastoral dwellers who could clear forests for the agricultural lands. The Company demarcated the Damini-i-Koh region in Jharkhand, basically the forested Rajmahal Hills area covering the districts of Godda, Sahebganj and Pakur.

They first encouraged the hill dwelling Mal Paharia tribes, to settle, who however refused to clear the forests and declined the offer. This led the Company to invite Santhals, then located primarily in Junglemahal region settled along the Subarnarekha river from Hazaribagh to Medinipur.

Driven by promises of land and better economic opportunities, the Santhals came to settle in large numbers not just from Junglemahal region, but even from Odisha.

Between 1830-50, the Santhal population in the region substantially rose from 3,000 to 83,00, which in turn resulted in an increase in the Company revenue. However the Santhals did not benefit in any way from this, as the Mahajans and Zamindars, along with the tax collectors, collectively called as Diku, who were hand in glove with the Company, began to exploit them.

Lending money at exorbitant rates of interest to the Santhals, grabbing their lands, forcing them into bonded labor, led to increasing resentment among them. The bonded labor was in two forms, kamioti by which the borrower had to work for the mahajan till loan repayment, and harwahi where apart from working for the mahajan also had to plough the fields.

The Zamindars on the other hand extracted huge rents from the Santhal peasants, while those who worked in the indigo plantations, had to slave for long hours, and extremely low wages.

The oppresion and indifference of the British administration to their woes, led a group of Santhals under Bir Singh Manjhi,Domin Manjhi to attack the Zamindars in 1854, and distribute the loot among the poorer lot.

Simultaneously, a chieftain called Margo Raja began cultivating a network of secret disciples throughout the Damin-i-koh, aiming to unite all Santals into a single body.

And in a way that would lead to the Santhal Revolt, that began on June 30, 1855 by the Murmu brothers Sidhu and Kahnu, who claimed to have received the word from their deity Thakur Bonga. And that very night some 10,000 Santhals gathered at Bhognadih, where the brothers announced as per their deity after the Lo Bir Baisi (tribal council) passed a resolution at Boda Darha in Sohraiya village, on the eastern part of Marang Buru (the Great Mountain), to launch the Santal Hul. .

“Slaughter all the mahajans and darogas, to banish the traders and zamindars and all rich Bengalis from their country, to sever their connection with the Damin-i-koh, and to fight all who resisted them, for the bullets of their enemies would be turned to water”.

The revolt was initiated from the sacred Jug Jaher Than (sacred grove) and Dishom Manjhi Than (seat of the traditional leader). Sidhu Murmu’s vision during the Santhal Hul wasn’t just to resist; it was to reclaim governance. What he and his fellow leaders attempted was nothing short of revolutionary: the creation of a parallel state, rooted in tribal justice and autonomy.

As reports of armed revolt began to flood in, the Company was caught by surprise. The District Magistrate of Bhagalpur reported that over 1000 Santals were in revolt, while the DM of Aurangabad, reported over 9000 gathering in Murdapur. By July 10, around 12,000 Santhals were assembling near Jangipur, and the Aurangabad magistrate later claimed they had occupied railway houses.

When a police party went to arrest the Santhal leaders on complaint of the Mahajans, they were attacked and a daroga was killed. This began the “Hul” that would soon spread to other regions like wildfire, as Zamindars, money lenders, were attacked, their property looted, and some of them executed.

The rebels advanced with a 1000 man force, reaching Kahalgaon by July 11, cutting off road and rail connections to Bhagalpur. Declaring the end of Company rule, they proclaimed the rule of the tribal suba.

Ignoring a company declaration to surrender, they routed a company of Paharia Rangers and inflicted a humiliating defeat on EIC troops at Narayanpur, killing several Indian officers and 25 sepoys. The victory boosted their morale, as the Santhals attacked villages from Rajmahal to Palassor, as many of the Zamindars, Mahajans took refuge in Rajmahal.

The Santals led by Siddhu and Kanhu, moved towards Pakur, Maheshpur, and Samserganj, with forces growing to 20,000 by mid-July. Rampurhat, Pulsa fell, as the Murmu brothers,organized their forces, granting titles like suba thakur and nazir to followers, forming a more structured leadership.

They were supported by a large number of smaller peasants and artisans, impoverished by the British rule. While the Gowalas supplied them with milk and other provisions, the Lohars made their weapons. Also smaller tribes like Kamars, Bagdis, Bagals supported the revolt.

Their aim was a fairer land systemcharging lower rents for Bhumij and Bengali peasants, a sharp contrast to the exploitative Company rule.

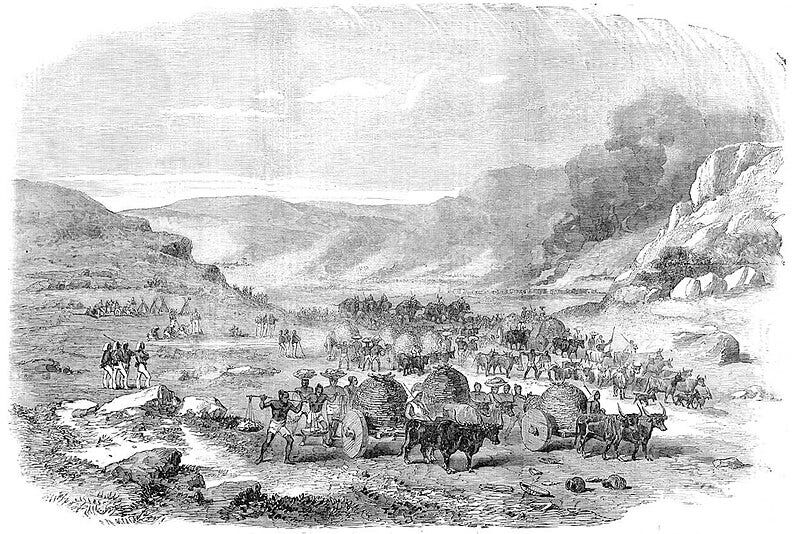

With the situation getting out of hand, the Company struck back, sending in a large number of troops to suppress the revolt. The Nawab of Murshidabad supplied war elephants to be used against the Santhals, while a bounty of Rs 10,000 was announced on Sidhu and Kanhu.

AC Bidwell was appointed as the Special Comissioner, as the Governor’s council authorized full scale military action. The plan was to secure strategic locations near the Ganges, restrict Santal movement north of the road, and block their retreat into the hills.

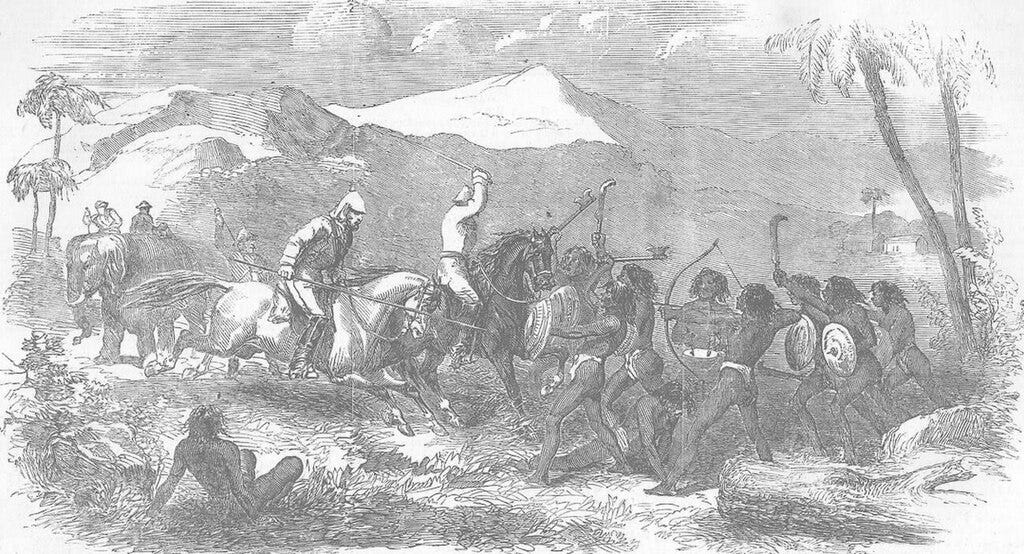

The turning point came on July 24, 1855, at Maheshpur, when the Company troops, fought with a 5000 strong Santhal force. The primitive weapons of the Santhals were no match to the artillery, as around 100 were killed, and most of the others fled.

Meanwhile Kanhu Murmu personally led an attack on Barhait, where the Company fired at the rebels, but failed to hit them. Though the Company won direct conflicts in Birbhum, they could not prevent the Santhals from regrouping.

In another skirmish around 8000 Santhals, ambushed an unit led by Lt. Tolmain, resulting in his death, and around 13 British soldiers dead, while 100 Santhals were killed. Another skirmish at Nangolia saw the Company, pushing the Santhals back, resulting in 200 casualties, as the revolt took one bloody turn now.

Towards end of July the British reorganized their forces, bringing in Major General G. W. A. Lloyd from Dinajpur, who set up a force consisting of 5 regiments of local infantry, Hill Rangers, some European troops, and cavalry. They moved into the Rajmahal countryside, splitting up the Santals, blocking the passages to the plains.

The Santhals meanwhile hit back with a series of hit and run attacks on the Company troops, as the British hit back with a martial law declaration. The Bhagalpur comissioner issued a proclamation on August 23, 1855 permitting the mass killing of Santhals. Eventually the Lt Governor, pressed the Governor General to declare martial law from Bhagalpur to Murshidabad, allowing for immediate execution of armed Santhals.

The Company now adopted a carrot and stick policy,promising lands and amnesty to those who surrendered.Sidhu Murmu was arrested and hanged on August 19, 1885 while Kanhu was arrested in 1886. The movement received a setback with the two brothers killed, and after six months it finally ended. Many Santhal villages were burnt down as punishment, and elephants used to tear down their homes.

The Santhal revolt though would lead to many other such tribal revolts in Jharkhand, Chattisgarh, Odisha against the British. As a consequence the British passed the Santhal Parganas Tenancy Act ,1876 that offered the tribals protection from exploitation by the non-tribals. It also prohibited sale of tribal land, and was continued even after Independence. A separate province of Santhal Parganas was created covering Bhagalpur, Purnea, Malda, Murshidabad, Birbhum, Bardwan, Manbhum, Hazaribagh, and Monghyr.