March 13,1940, Caxton Hall, London

Caxton Hall a building located near to Westminster, which primarily hosted political events. It's other use for high society celebrities to register a civil marriage. On this date, though it would be creating a history in another way. A joint meeting of the East Indian Association and Central Asian Society( now Royal Society for Asian Affairs) was scheduled to be held.

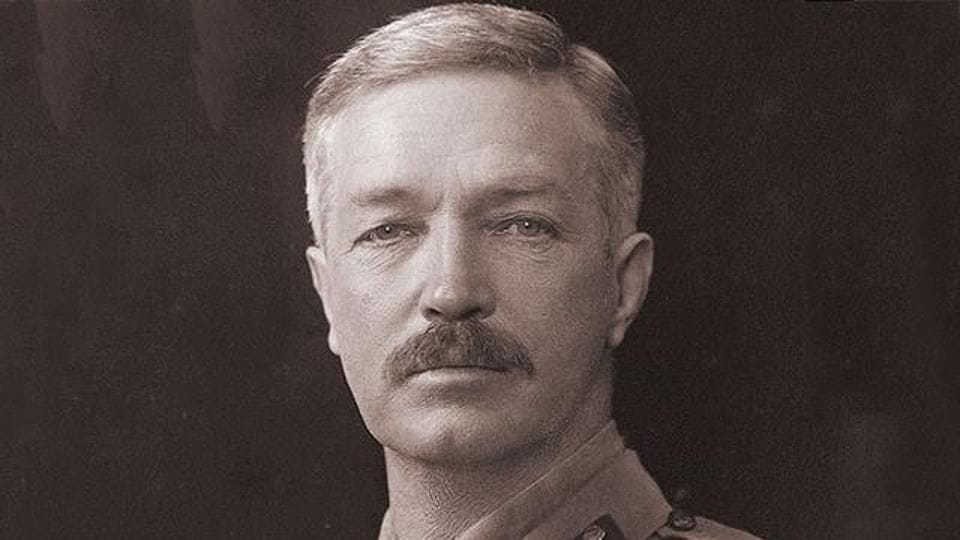

One of the speakers was a certain Michael O'Dwyer. Hailing from Ireland's Tipperary County, son of a poor farmer, he had joined the Indian Civil Service. He would however be more notorious for his conduct as Lt.Governor of Punjab from 1912-19. In a region that was burning with protests against British imperialism, Dwyer, was noted for his harsh crackdowns and often draconian laws.

Nothing however would beat the brutality of what happened on April 13,1919 when 379 unarmed civilians were massacred at what was called Jallianwala Bagh, a walled garden in Amritsar. The massacre at Jallianwala was led by Brig.Gen Reginald Edward Dyer.

Though it was Brigadier-General Dyer who ordered the firing, it was Michael O’Dwyer who sanctioned the spirit of the act, defending it as a necessary blow to “prevent rebellion.” In the days that followed, O’Dwyer imposed martial law across Punjab, backdating it to March 30, 1919—a legal sleight of hand to justify the unjustifiable.

Civilians were subjected to grotesque punishments: in the narrow Kucha Kurrichhan lane where a British missionary had been attacked, Indian men were forced to crawl on their bellies as a form of collective penance. Public floggings became routine. Entire neighborhoods were placed under curfew, and aerial bombings were carried out in Gujranwala to “quell unrest”. The message was clear: the empire would rule not just with force, but with humiliation.

These acts didn’t suppress rebellion—they ignited it. Across Punjab, a generation of young Indians—many of them witnesses to the bloodshed—were radicalized. The soil of Amritsar, soaked in blood, became a crucible for revolution.

One of them was sitting in that very gathering, a revolver concealed in his jacket pocket, waiting for O'Dwyer to come on to the stage. As Michael O’Dwyer approached the podium, he rose and fired. One bullet pierced O’Dwyer’s heart and lung; the other tore through his kidneys. The former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab collapsed instantly.

The man who calmly stood up and fired those two shots was Udham Singh, a survivor of Jallianwala Bagh, who had waited 21 years for that moment. Concealing a revolver inside a hollowed-out book, he had entered Caxton Hall under the name of his wife, blending into the audience like any other guest.

When arrested, he reportedly said, “I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it... I am happy that I have done the job. I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country.”

In that moment, Caxton Hall—once a venue for civil unions and polite discourse—became the stage for a solitary act of justice, carried out not in rage, but in solemn resolve.

Born on December 26, 1899, in the dusty lanes of Sunam in Punjab’s Sangrur district, Sher Singh’s early life was marked by hardship. His father, Tehal Singh, a humble railway crossing watchman in the village of Upali, and his mother Narain Kaur, passed away when he was still a child. Orphaned alongside his elder brother Mukta Singh, the two boys were admitted to the Central Khalsa Orphanage in Amritsar on October 24, 1907.

There, amid the austere dormitories and early morning prayers, Sher Singh was reborn as Udham Singh—“Udham” meaning upheaval, a name that would one day echo through the halls of British power. His brother Mukta became “Sadhu Singh,” though tragedy would strike again when Mukta died in 1917, leaving Udham alone once more.

Despite the grief, Udham Singh persevered. He passed his matriculation exam in 1918 and left the orphanage in 1919, just months before the massacre that would define his life.

1919—Punjab stood on the edge of a storm. The passage of the Rowlatt Act had ignited a wave of protests across the province.

In Amritsar, the arrest and secret deportation of two beloved nationalist leaders—Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr. Satyapal—sparked outrage. On April 13, the day of Baisakhi, thousands gathered at Jallianwala Bagh, a walled garden near the Golden Temple, to protest peacefully and demand their release.

But what was meant to be a gathering of voices became a valley of death.

Without warning, Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer marched in with 90 soldiers, blocked the only exit, and ordered them to open fire. For ten long minutes, bullets rained down on the unarmed crowd. Over 1,500 were injured, and hundreds died, many leaping into the well at the center of the garden to escape the gunfire. Dyer later admitted he had come not to disperse the crowd, but to “punish them.”

And behind him, in the shadows of power, stood Lieutenant Governor Michael O’Dwyer, who not only endorsed the massacre but praised it as a necessary act to preserve imperial order.

Among the survivors was Udham Singh. That day, something inside him changed forever. The blood of innocents, spilled on sacred soil, became the fire that would fuel his long, patient path to vengeance.

Jallianwala Bagh had not just wounded him—it had transformed him. The blood-soaked soil of Amritsar became the crucible in which Sher Singh was forged into a revolutionary.

In the early 1920s, he left for the US, where he came into contact with the Ghadar Party, a global network of Indian revolutionaries committed to overthrowing British rule. Their fiery rhetoric and underground publications stirred something deep within him.

Around the same time, he was drawn to the Babbar Akalis, a militant offshoot of the Akali movement that rejected non-violence and sought to restore Sikh sovereignty through armed resistance. Their defiance, rooted in memory and martyrdom, left a lasting impression.

In 1924, responding to a call from Bhagat Singh, Udham Singh returned to India with a small group of associates and a cache of smuggled revolvers. But before their plans could take shape, he was arrested in Amritsar for possession of unlicensed arms and seditious literature. He was sentenced to four years in prison.

Upon his release in 1931, he returned to Amritsar and took up work as a signboard painter—a humble trade that masked a restless spirit. It was during this period that he adopted the name Ram Muhammad Singh Azad.

Haunted by memory, guided by ideology, Udham Singh lived under the shadow of surveillance after his release in 1931.

Slipping away to Kashmir, he evaded the Punjab Police and made his way to Germany in 1934. From there, he wandered across Europe—Italy, France, Austria, Poland—always under assumed names, always watching, waiting.

His travels weren’t aimless. They were part of a deliberate strategy to reach London, the heart of the empire, where his target—Michael O’Dwyer—still moved freely, unrepentant.

Singh’s ideological compass was shaped not only by Bhagat Singh, whom he revered as a guru, but also by the Russian Revolution. He often carried with him a Punjabi booklet on the Bolshevik uprising, a symbol of his belief in the power of the oppressed to rise.

His admiration for the revolution wasn’t just theoretical—he saw in it a model for India’s liberation, a blueprint for dismantling imperialism at its root.

In London, he lived modestly—working as a signboard painter, mechanic, even appearing as an extra in films like Elephant Boy and The Four Feathers. But beneath the surface, he was preparing. He acquired a six-chamber revolver, hollowed out a book to conceal it, and waited for the right moment.

He finally got a chance to avenge Jallianwala Bagh, the revolver to him was given by Puran Singh, hailing from Punjab's Malwa region. As the shots rang out in Caxton Hall, and Dwyer fell to the ground, Udham Singh stood his ground, and surrendered to the police.

I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it. He was the real culprit. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him. For full 21 years, I have been trying to wreak vengeance. I am happy that I have done the job. I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country. I have seen my people starving in India under the British rule. I have protested against this, it was my duty. What a greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland?- Udham Singh on O'Dwyer

On April 1, 1940, Udham Singh was charged with murder of O'Dwyer. On June 4, 1940, he stood for trial at the Central Criminal Court, in London's Old Bailey, before Judge Atkinson.

When Judge Atkinson asked if he had anything to say before sentencing, Udham Singh rose, put on his glasses, and began to read from a prepared statement—a defiant, impassioned speech that the British authorities tried to suppress under the Emergency Powers Act.

He declared:

“I do not care about sentence of death. It means nothing at all. I do not care about dying or anything. I am dying for a purpose. We are suffering from the British Empire... I am proud to die to free my native land, and I hope that when I am gone, in my place will come thousands of my countrymen to drive you dirty dogs out...”

He thumped the rail of the dock and shouted:

“Inquilab! Inquilab! Inquilab!”

(Revolution! Revolution! Revolution!)

And then, with fire still in his voice:

I say down with British Imperialism. You say India do not have peace. We have only slavery. Generations of so called civilization has [have] brought for us everything filthy and degenerating known to the human race. All you have to do is read your own history. If you have any human decency about you, you should die with shame. The brutality and bloodthirsty way in which the so called intellectuals who call themselves rulers of civilization in the world are of bastard blood…’

The judge tried to silence him, but Singh would not be denied. His words, though censored at the time, would echo across generations as a testament to the fury of the colonized and the courage of a man who turned grief into revolution.

Atkinson told him, he was not interested in a political speech, and Udham Singh, said he just wanted to protest. Udham Singh then remarked he had something to read, the Judge told him, he was fine, as long as he gave a reason why no sentence should be passed.

Udham Singh, calm but resolute, put on his glasses, pulled out a folded sheet of paper, and began to read. Judge Atkinson interrupted, warning him not to make a political speech. Singh replied, “You asked me if I had anything to say. I am saying it. I want to protest.” When the judge insisted he stick to the point, Singh thundered:

‘I do not care about sentence of death. It means nothing at all. I do not care about dying or anything. I do not worry about it at all. I am dying for a purpose.We are suffering from the British Empire.I am not afraid to die. I am proud to die, to have to free my native land and I hope that when I am gone, I hope that in my place will come thousands of my countrymen to drive you dirty dogs out; to free my country.’

‘Machine guns on the streets of India mow down thousands of poor women and children wherever your so-called flag of democracy and Christianity flies.’

He claimed his fight was not against the English people, it was against the conduct of the British Government and British imperialism. When he finished his speech, he raised slogans against the British rule and spat on the solicitor's desk before leaving.

On July 31, 1940, at Pentonville Prison in London, he was hanged. The British authorities buried his body in the prison grounds, far from the land he had loved and bled for. But history would not let him rest in exile.

Mahatma Gandhi condemned Udham Singh’s act, calling it an “act of political insanity,” while Jawaharlal Nehru, writing in the National Herald, expressed regret over the assassination. Yet, not all within the Congress shared that view.

The Punjab Provincial Congress Committee refused to denounce Singh, recognizing the deep anguish that had driven him. The Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA), the ideological heir to Bhagat Singh’s vision, stood firmly behind Udham Singh and publicly rebuked Gandhi’s statement, calling it a betrayal of revolutionary sacrifice.

Support for Singh wasn’t confined to India. International media, including The Times of London, described his act as “an expression of the pent-up fury of the downtrodden”. To many across the world, Singh was not a madman, but a man who had carried the weight of a massacre for 21 years—and finally laid it down with two bullets and a cry for justice.

In 1974, honoring his final wish, his ashes were returned to India. They were brought to his hometown of Sunam in Punjab, where he was cremated with full honors. A portion of his ashes was scattered at Jallianwala Bagh, the site of the massacre that had shaped his destiny.

One of India’s great sons had fired a final shot—not in hatred, but in memory. And in doing so, Shaheed Udham Singh became a symbol of unflinching resolve, a martyr whose silence spoke louder than a thousand speeches.

Revolutionary, freedom fighter, inspiring millions of people. Thank you for sharing 🙏